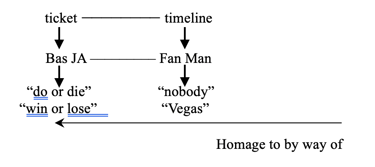

1.

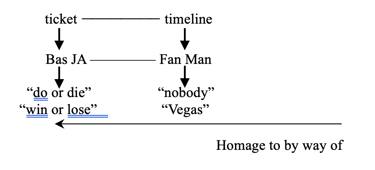

In a critique session, an artist once asked me “what if I don’t want to look into the hole?” pointing at my piece, a hole on the wall.[1] And the same question can take other forms, “what if I don’t want to look at a Mondrian, a Monet, a Malevich?” or “what if I don’t want to go to a contemporary art museum?” It’s a good question worth not answering. You have to know the answer for yourself. As far as it concerns us here, encountering art starts with wanting to look into the hole.

Let this beginning set the framework for us. We are already looking in.

Before it is a work of art, a hole on the wall is an ordinary-object. It’s the wanting-to-participate that makes the hole on the wall a place of interaction between you and the other,[2] an art-substrate. The wanting to participate subjectifies the audience to signification along with its rules and limits. The creator too, brought in by his intention (i.e., his desire manifested through signification), is subjected to these norms.

The art-substrate is the place of interaction between the author and the audience.[3] Author comes to the space by arousing a signifying chain and the audience comes in with an understanding of how the signifiers function in relation to one another and in relation to the discourse of art as a whole. Taking the ordinary-object as an art-substrate is to allow oneself to enter this space of interaction, a meaning producing space in which participants are inserted––what we will call the discourse, the symbolic structure that stands for Lacan’s big Other. If the art-object is reduced to the meaning produced within this interactive space, that is if the art-object is attainable through a one-to-one signification between a signifier and what it signifies (its referent), a view held by the Logical Positivists, then art is nothing but a nexus of symbolic relations and fairly within the reach of its participants. In which case our job is done here, and mastering the symbolic relation in art would suffice for both creation and interpretation. Our engagement here rejects the conception that treats the discourse of art as a medium for producing meaning through one-to-one signification and situates the art-object within a signifying chain. Instead, we embrace the idea that art extends over the boundaries of the given structure to engage the extremes of life, an excess that exceeds discourse.[4] That which we are after here––i.e., the art-object or in the case of language the metonymic object––is always somewhere else, displaced. Work of art, which is preoccupied with this displacement of its object, points at the beyond of its discourse; it disrupts norms, adheres to its own rules, and communicates through a veil of signification. This reach for the beyond pushes the art-object to remoteness, deems it immediately inaccessible. Our role here is to seek access.

We should already see similarities between the set-forth task and that of psychoanalysis. The structure that I am articulating here, carries qualities akin to Lacan’s understanding of the symbolic structure of language. In analysis for Lacan, language is not a mere form of communication but a symbolic manifestation that points at what is beyond it, the unconscious. The reaching for the beyond involves an investigation of metaphoric and metonymic structure of speech. In general, it is through understanding the relationships between signifiers that we attain meaning, and it is in locating an absence in the chain of signification that we work our way toward the displaced placeholder of desire,[5] the metonymic object that for us resembles the art-object:

This two-sided mystery is linked to the fact that the truth can be evoked only in that dimension of alibi which all ‘realism’ in creative works take its virtue from metonymy; it is likewise linked to this other fact that we accede to meaning only through the double twist of metaphor when we have the one and only key: the S and the s of the Saussurian algorithm are not on the same level, and man only eludes himself when he believes his true place is at their axis, which is nowhere.[6]

With regard to common works of art, the art-object is revealed by understanding the relationship between the signifiers.[7] Thus, with those pieces we seek the art-object from within the signifying chain.[8] In those pieces, in order, the meaning is always deferred, and the art-object is always elsewhere, making the object of the work always unattainable as in any attempt to grasp it pulls you into a new chain of signification.[9] Analogous to the art-object, Lacan schematizes the metonymic object as “the object that cannot be named and that is only named through its connections.” It’s only with regard to a distinct group of works that the art-object reveals itself to us in a form of a strike similar to that of wits or slippages. This strike—which we will call the ‘experience of encounter’––functions like a hole through the veil of discourse and directly exposes us to the displaced placeholder of desire. Four things stand out as for the similarity between wits and slippages on one hand and metonymic works of art on the other: one, the interlocutor’s (target audience’s) close familiarity with the elements involved is necessary, otherwise the wit loses its striking power. Two, explaining the mechanics of a joke alone is insufficient for the joke to land. Three, strike has a crucial function in creating the desired result in the target audience—i.e., the response following its reception: laughter, feeling insufficient, gratitude, or even something expressive and ineffable. Lastly, unlike common works of art, the revealing of the art-object is not merely a faint clue at a displaced object but rather a revealing that allows for a direct experience of the art-object through the hole of signification. “Witticisms are located at such an elevated level of signifying elaboration that Freud paused there to perceive a specific example of formations of the unconscious” (FU 38). Wits, and in some cases word slips, are so far out there that they eviscerate the unconscious better than the linguistic analysis of straightforward speech which is levels removed from the symbolic matters of the unconscious. Witticism, in a way, is the unconscious’ playful interruption in speech.

I want to discuss three instances, two of which amounted to a work of art, and the other to a disappointment. In all three instances we are faced with a number of symbolic elements, those which we will call hooks, and a metonymic parallel, which are simultaneously inactive, but become apparent once these elements surface. The question is, how might we encounter what I would like to call metonymic works of art?

The goal here isn’t to psychoanalyze these works of art but to encounter them using the structure of understanding wits and slippages, that Lacan has already laid out––works that otherwise might go unnoticed. Thus, this reading is not derived by psychoanalysis but is inspired by it. This is not a comparative analysis; we place our focus on these instances instead.

2.

The first instance is a commissioned piece, titled “Cry,” for an art collector friend named J. The work is an Argon gas neon piece that reads “Cry” in reverse with an ultra-thin hair line, belonging to J’s son, forming a square around it and striking through the word Cry, indicating the negation of the command. The piece consists of two juxtaposing commands, Cry and Don’t Cry. The two commands do not appear at the same time; when standing in front of the piece J sees the command in reverse with focus on the hair line around it. Bringing forth the idea of his son’s role in his life assumes authority in negating the command. When sitting in the bathtub, the hairline is no longer perceivable, and the command finds a more friendly and decorative function, a playful presentation of the word cry that reads in reverse. Only in the mirror, perhaps when brushing teeth, Cry appears as a command but without the hairline, eliminating the sustenance and the familial, making the command even more ruthless and authoritative.

J wanted a piece that would not get old. If you have had a bright neon piece in your place you would sympathize with his request shadowed by the foreboding that its novelty would wear thin in no time. To fulfill his request the piece was designed to never appear in full, but to appear in part in different stages and occasions. J described his bathroom as a temple, an intimate space where he is most vulnerable.

We have to pay attention to the command here. I am explaining that J described his bathroom as an intimate space, a temple, and I had the choice to either treat it as sacred or to take an authoritative role. I went with the latter by bringing out the brute force of being in a temple, the reality of a personal space where one can be vulnerable—weighed by the terror of the day in front of the mirror, exposed in the tub, perhaps taking a restless break from work, etc. these were the circumstances in which the piece had impact. To be vulnerable, after all, is relevant to but not the same as being comfortable. The sense of intimacy that belonged to J’s bathroom resembled and was founded on the former sentiment. The idea of a command in a personal space assumes this position, and to choose a command, cry/don’t cry was suggested to me by an art accomplice friend name Cory, inspired by my proximity to J’s life and knowing that, given the recent events, which are besides of the interest of this paper, the commands will affect him similar to an inner voice. All we need to know is the immense weight of these events that enable the command to be effective.

Taking on such an interpersonal approach in constructing the concept of the piece makes the personal relation to the contextual elements of the work inseparable from the experience of the work. The piece is designed for an intimate and personal encounter and makes little to no sense outside of its context, yet seeing the work from the outside is inseparable from its art-object. J has the context and you, the reader, see the work from the outside, each missing something necessary. The work consists of two distinct planes, and the apprehension of the work––i.e., unconcealing the art-object––necessitates meeting the work on both planes. Lacan writes, “it’s impossible to represent the signifier, the signified and the subject on the same plane,” suggesting that the only meaning is metaphoric meaning, and the only object is metonymic object. Experiencing a level of closeness with the piece and understanding the conceptual framework within which the piece operates, pertain to different positions, nevertheless apprehension of the piece requires one to operate on both levels, being intimate from within and distant enough to perceive all signifiers from without. J’s experience of the work is designed to be limited to operating on a single plane, while reception from a wide audience is eliminated altogether. The art-object that we work to unconceal from this piece is only for the position of the author to behold, creating an impossible position for the audience. The only way that the piece can exist outside of J’s bathroom and be given a wide audience is by writing about it. Where we are with this task is at the level of explanation. Explanation will not recover the piece as a metonymic work of art. Wit either fails or succeeds. Either way, explanation cannot substitute for it. The do or die is the predicament of this reiteration. Thus, to bring Cry to a wide audience, this writing has to also function as a stand-alone reiteration of the work Cry. It can be read as a piece of its own rather than an analysis or exegesis. Thereof our art-object is not in the writing but placed elsewhere, revealing itself once we recognize the elements of this writing as signifiers in a chain of signification of their own. Neither will it amount to a sentence nor a description, revealing itself wholistically to a receptive encounter. Lacan has told us that you have to know what is presented to you is a wit in order to engage with it as a wit; for a similar reason I set in plain sight this writing’s dual function: a reiteration of the piece Cry, which resembles the structure of a witticism, and a strong suggestion how to understand metonymic works of art.

J’s encounter with the work functions as an element within the work. J is the intended audience, yet does his experience touch upon the art-object? The piece functions according to the idea that he does not. J’s connection to the piece extends as far as the effect that the piece has on him, in different stages and gradually through time, and similar to a decorative object—arthood for J functions as a label that helps to categorize the ordinary object in dispute (a piece of neon with hair around it) as an object of appreciation, this categorization, however, does not penetrate the deeper dimensions of the work that we are after. His role as the intended audience is to be fully submerged in the physical and mental space that the piece occupies, yet to be unaware of the underlying conceptual elements that shape the outer structure of the work, the structure that he himself is a part of, and that you as the reader see from the outside. J experiences the piece and is affected by the choices involved in the conception of the work without seeing himself as a signifying element within a chain of signifiers from which the art-object is missing and placed elsewhere. He remains at the level of signification, lacking crucial pieces that would amount to a whole: without stepping outside of the signifying chain and seeing himself as another signifier, a functioning whole that points at the art-object that does not appear. The art object operates in a realm that resists exposure through description, though revealing itself only through a complex and unprecedented proximity of signifiers. How might I then transpose this piece again into a chain of signification in order for it to reach an audience beyond Cory and I, as co-authors of “Cry?” In seeking the metonymic object through language, we find ourselves in a process of what Lacan calls “formation of unconscious” that like the unconscious, is not engineered, but an organic proximity of signifiers that in their proximity erupt into the exposure or direct experience of an art object’s visceral absence. The only way for a direct and private experience of an art object to reveal itself to a new audience is through the unconscious relation between other instances of riddle and slippage. Only through this second puzzle can the reader experience the rendering of a newly displaced art object. The second puzzle, the do or die, is pointing at a predicament between the wider audience, the reader, with the displaced art object of this writing.

“Why does J’s role take on such restricted position?” you might ask. There is a long tradition of making works of art with dimensions that are hidden to a target audience, and this approach trends in most of my work. This is a veil on top of the veil of signification. Esoterism in creating a multi-level content allows for operating on a level that is only of interest to a few. Articulated in different plains, the esoteric work on the surface plane appears straightforward and unchallenging, hiding a more articulated dimension from its target audience. Arthur M. Melzer provides four reasons for why specialists are gravitated toward esoterism, two of which are applicable to our case stated: to protect the audience from the boredom of the content that might be useless or else destructive to them, and the lack of interest in certain content that juxtapose the lifestyle of the target audience.[10] It’s only artists, of course not all, that have developed expectations of art. Part of the role of the author in conceiving a commissioned piece as such is to pay close attention to what is requested from the work. The piece delivers exactly what J asked for: a multi-dimensional piece displaying a neon text that remains timeless. It comes without saying that a quality is always expected from a work of art, whether instructed or not, that is to be indelible through experience.

I already described J’s interaction with the piece as an ordinary interaction with an ordinary-object that for him carries the label, work of art––what other theorists mistakenly call the artwork, assuming that something is already a work of art and stripping the encounter with the work from a process of becoming art. His interaction itself operates as a signifier in a signifying chain. He does not get at the art-object, and the art-object does not strike him either.

In another instance, it is a gallerist friend, Holly, who misses the strike. What distinguishes the two instances, is that J experiences exactly what is available and intended for him and the art-object remains displaced and irrelevant to his experience as it is an art-object relevant to the position of the author––mutually occupied by Cory and me. Conversely, with the gallerist friend the metonymic object is exposed through a slippage, but reads it as an unworthy mistake, reducing the truth to an error in the realm of the real.

Holly tells me she goes to the space neighboring her gallery, a studio belonging to a man named George. “His studio smells like ferrets,” says Holly. She relays to me that George is currently being evicted from the space. I reply with pitching an idea for a future show at her gallery exhibiting 100 living parrots loose in her space, titling it Trust George. Holly plays along with the idea until she finally realizes the slip, at which point she loses interest in the work all together. Lacan speaks extensively about the significance of verbal slippages, being far from mere accidents, especially for multi-lingual speakers (FU 30–52). When I had my show in Holly’s space prior to the conversation, George was the only person who insisted on offering his help, lending me a tin can of rubbing alcohol, telling me it is the purest and I cannot find it elsewhere, all to remove residue of window film, remnants from the previous show. With the example of famillionaire, Lacan tells us that what is excluded or ought to be excluded from the deciphering of the unconscious, is exactly stated, the familiar. In other words, with regards to wits what ought to be excluded is what is given at face value. The metonymic object is never what is in plain sight (FU 44–6). Holly does take what I said at face value, in perhaps a similar way she takes her encounter with George at face value; in missing what is absent, she misses what can be revealed. My response to George’s eviction is tossing the idea of an exhibition at her, though what she sees is that George’s studio smells like ferrets not parrots. In Trust George, I’m offering a rough idea which would be ambitious to pull off; 100 parrots free in a white cube. Lacan does say that wit has to be explicit, read as a wit in order to be understood as a wit. There is nothing inconclusive about that for Holly. If I show 100 living Ferrets would that make a difference? Take 100 zebras or pigs, for all we care, there is a slippage that indicates beyond it. You cannot point at a gaze, because all you would be pointing at is a pair of eyes.

A horse calls a circus owner, saying that he wants to join the circus. The owner asks, do you have any talents that might qualify you? The horse responds, I can stand on two feet, I can jump through a hoop of fire etc. Regardless of what the horse says, the owner responds that it’s not enough to qualify him to join their show. Finally, the horse says, I am speaking to you in plain English, is that not enough? I am revealing something with 100 parrots, and all one can see is that it should be 100 ferrets, not parrots? What might one need to do to bring to another’s attention that there might be a “something missing” to get across.

The idea was never elaborated from this point on, and no manifestation of the show came to fruition. Nevertheless, there is a displaced metonymic object at play in this example. Unlike as is seen in J’s case, a position for a wider interlocuter is possible. In missing something essential about George, an experience of George beyond the superficial, likewise an experience of language beyond its referent, Holly and I experience a mutual disappointment in one another. As mentioned before, I won’t be able to name the metonymic object, but there is something lost in this interaction that serves as the displaced placeholder of my desire. In each instance, I am trying to tell someone something I am unable to express, bringing me to the starting point, a sense of disappointment.

3.

The last instance is about one of Cory’s own works.

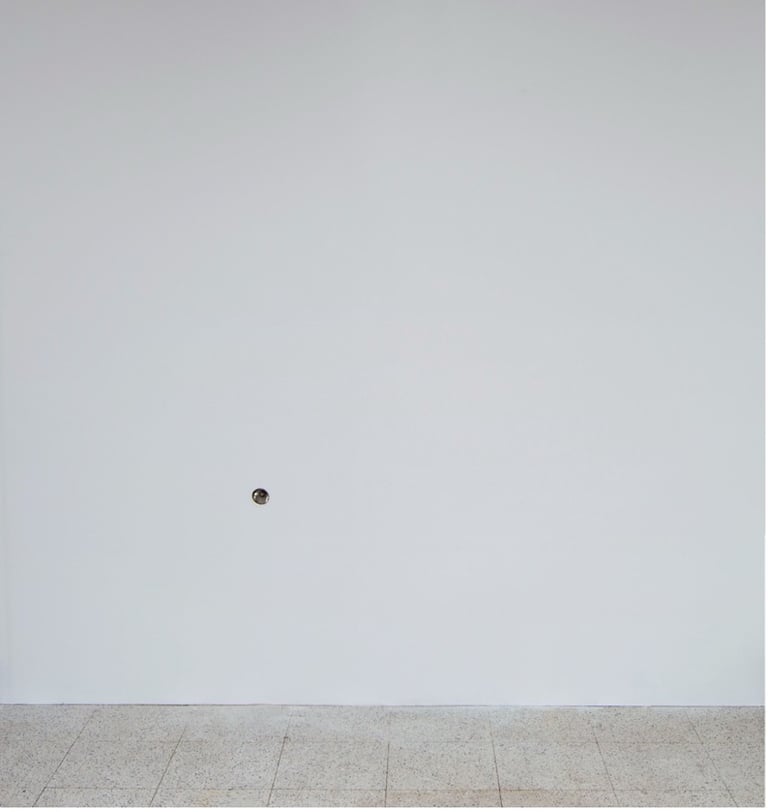

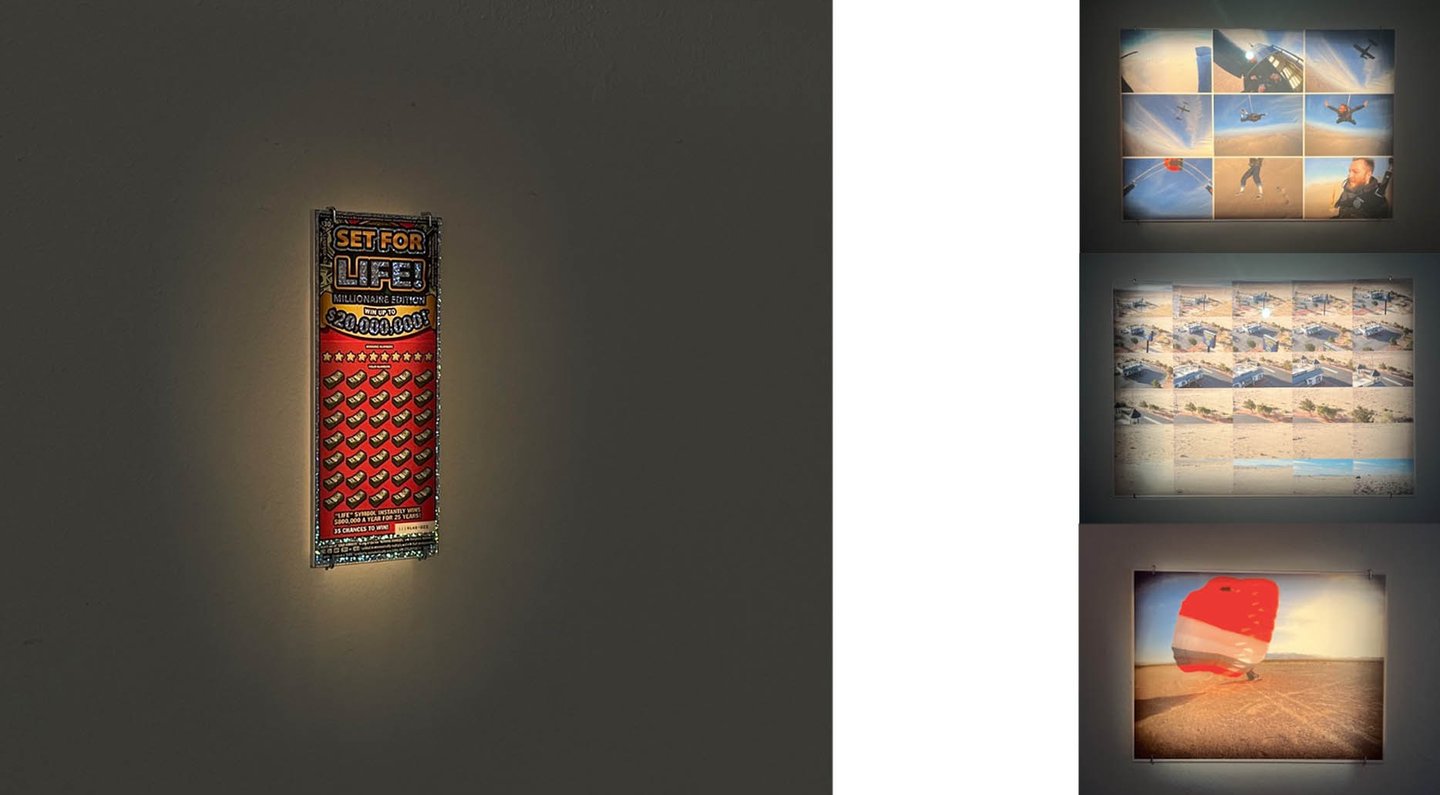

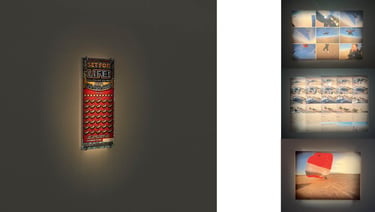

At age 5, during a live boxing match on television, Cory sees a man, self-proclaimed as the Fan Man, parachuting into Evander Holyfield and Riddick Bowe’s boxing match in an open field rink at Ceasars Palace in Las Vegas. About 28 years later, Cory jumps out of a plane in Las Vegas. He documents the timeline of his landing at a lottery location at the border of California and Nevada, where he acquires a lottery ticket to later include in an exhibition titled Grooming the Ocean Wave: The Winning Ticket. The exhibition is at a space run by the same gallerist, with whom I experienced the sense of disappointment.

Do or Die

Notes:

[1] Titled A Realistic Drawing of the Sun, this work of art, part of a group exhibition, is a hole in the wall concealing a bright light bulb activated by a motion sensor, hidden in plain sight. The strong light creates an afterimage—a yellow circle resembling the experience of looking at the sun—when a curious viewer peers through the hole. Designed to remain hidden, the piece invites interaction, prompting reflection on the audience’s willingness to engage with art. Even missing the piece functions as an element within the work.

[2] The participant on the other end of the signifying chain. Thereof from the position of the creator the other is the viewer, and vice versa.

[3] To encompass all creative mediums, hereon we will refer to the creator/conceiver of any kind of art-object as the author and the consumers of any kind of art-object as the audience.

[4] Thus, although philosophy aspires to be sum of knowledge, as Hegel envisages the subject, philosophy can never be ‘the sum of experiences’. See George Bataille, “Sanctity, Eroticism, and Solitude,” in The Continental Aesthetics Reader, ed. Clive Cazeaux (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 339–48.

[5] See Jacques Lacan, “The Famillionaire,” in Formation of the Unconscious, Book V of The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, trans. Russell Grigg, ed. Jacques-Alain Miler (Malden: Polity, 2017), pp. 14–5; and Jacques Lacan, “The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious or Reason Since Freud,” in The Continental Aesthetics Reader, ed. Clive Cazeaux (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 351–69.

[6] Jacques Lacan, “The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious or Reason Since Freud,” in The Continental Aesthetics Reader, ed. Clive Cazeaux (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 364.

[7] Similarly, in analysis it is the task of the analyst to trace the symbolic formation of the unconscious through the communication of the ego, a linguistic layer that functions like a curtain between the analyst and the unconscious of the interlocutor. Lacan claims that metonymy gives realism in creative works its power. By “realism,” he’s pointing to art, literature, and other forms that seem to represent reality directly. But in Lacan’s view, these representations are only ever partial, moving from one element to another (like a chain of details that conjures a scene). This metonymic structure creates an alibi for truth—suggesting truth indirectly, by association, without fully capturing it. The sense of realism comes from this continuity of associations, giving the illusion of a seamless reality. "The presence of the unconscious, being situated in the locus of the Other, can be found in every discourse, in its enunciation.” One of which being artistic enunciation. "What the unconscious brings back to our attention is the law by which enunciation can never be reduced to what is enunciated in any discourse." See Jacques Lacan, Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: WW Norton, 2007), respectively p. 834, and p. 892.

[8] In another work I explain that “gaining access to the art-object” is the very process of conceptualizing the art-object, consequently both creation and the interpretation of a work of art should be understood as a single task of getting at the art-object. The idea is roughly this: an art-object is negotiated in a dialectic between author and audience, where in encountering an ordinary-object they make a candidate of becoming an art-object. Thus, the art-substrate functions as a platform for getting at the art-object which is placed elsewhere.

[9] See Jacques Lacan, Formation of the Unconscious, Book V of The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, trans. Russell Grigg, ed. Jacques-Alain Miler (Malden: Polity, 2017), p. 52; henceforth FU, followed by page number.

[10] See Arthur M. Melzer, Philosophy Between the Lines: The Lost History of Esoteric Writing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

[11] Text appears in the Handout of the show titled Grooming the Ocean Wave: The Winning Ticket by Cory McMahon.

Grooming the Ocean Wave: The Winning Ticket

It is in this order that the elements of Cory’s show appear. There is an unscratched ticket with slightest probability of being the winning ticket. Facing the ticket on the opposing wall is the documented timeline of his jump and landing. Both walls represent duels winning versus losing, living versus dying. There is slim chance to win, likewise a slim chance that your parachute might fail. Slim chance to win faces the slim chance to die. Both duels deal with probability too little to mention, too significant to ignore. What is clear upon entering the space is that things are put into comparison, juxtaposition, tension. Buying into the idea that there might be a comparison via the spatial arrangement of elements, it becomes difficult to not apply the same lens of comparison to a handout that accompanies the show, juxtaposing two events, that of the Fan Man and the final art piece of Bas Jan Ader, in which he set out to sail from France to UK and was never seen again. It might prove of use to versify yourself with the style and work of Bas Jan Ader. In the case of Fan Man and Jan Ader’s final work, there is a sense of peril, not dissimilar to watching Alain Robert scale the Sears Tower, running through the probability of a wrong move. In both cases, there is so much at stake, the Fan Man in inserting himself into a nationally broadcasted event by jumping out of a plane, and Jan Ader exposing the dual in art by dueling death. It is along these lines that Cory says “Art is life or death for an artist . . . The artist's life frames all aspects as potential material.”[1]

A subtle homage takes shape as these external elements fall together in alignment, the unscratched ticket and Bas Jan Ader’s final piece amount to a matter concerning win or lose, do or die, gambles of monumental proportion. Cory’s rendered timeline of the jump aligns with the Fan Man’s jump in their shared locality––“Vegas” as an element contributes an anonymity of place that breeds a distinct tragic hero, to which a paper could be devoted but we will leave at the uncle in the trailer that smells of ash tray, talking about how he will make it big, a “nobody” asserting himself––in the fading memory of the jump, jumper, perhaps artist, perhaps writer. The homage is made by way of the Fan Man, mediating the relation between Cory and Bas Jan Ader. In other words, the homage is made by way of the ‘Vegas,’ and the ‘nobody’ as signifiers.

The encounter with art is a moment of crisis. Out of an incredibly thin probability, Cory runs into Bas Jan Ader’s widow in the streets of New York, during a period in which he has considered how interesting it would be to meet her, and before the showing of his piece Grooming the Ocean Wave: The Winning Ticket. Cory is able to see himself in Bas Jan Ader’s position, an intimacy between artists who have not met brings into sharp focus the distinguishing circumstances of their gamble, their disparate though mutually active relationships with do or die. ‘He’ is placing a bet on ‘his’ life. Art as an interrogation of crisis involves every aspect of ‘his’ life. The gamble one makes in placing these works of art in proximity is hidden from ‘him’, as it is hidden from us. This is what I’m getting at here: As Cory tried to tell us, “is that not what art is all about?” Is that not the restless/tireless duel with art?

The displaced object reveals itself when the work boils down to a set of personal circumstances: an artist’s personal matters have reached a state of crisis, and the artist’s wrestling with these matters has revealed itself in extreme measures through art, practices that bring the artist close to another artist. A perpetually vulnerable state asserts itself through the doing, whether it be a piece which requires one to jump from a plane or sitting down to write a paper about it. In that assertion, an active relationship to dissatisfaction is revealed, a relationship with disappointment that ultimately indicates inward by being asserted outward. Satisfaction with one’s own work is ever displaced, the search for which is propped by the lurking terror that one might have punctured the barrier between self and other, looked into that hole, for nothing. I said that Cory’s work boils down to an anxiety over personal matters. Is that it? The excavation of Cory’s piece displaces something. That displaced something pertains to the predicament of do or die that is relevant to both Cory and me, providing a directionality to signifiers gleaned from the other instances relayed in this paper, which offers up a new chain of signification. Here I am going to do what I warned you against. What is the work about, a personal matter? What if I don’t care? You ought to answer that for yourself, and it is too late anyway: “we are already looking in.”

4.

We ought to wonder, is it by mere accident that the three instances find home in this writing? Is it a mere slip? Clues for an answer were already provided in an earlier remark, that the piece is intended to serve a dual function, as a strong suggestion of how to understand what I have called metonymic works of art, and as a reiteration of the piece “Cry,” the first iteration of which, as we discussed, had impossible criterion for a wide audience. Thus, one should think of the composing elements of this paper, the instances and the information revealed with each, as symbolic elements of yet another piece that come together to make up a symbolic structure anew. For instance, by using the ways that I have revealed in unpacking the instances, one could think of the sense of disappointment brought up in the instance with the gallerist as the joint connection between the other two instances, “Cry” and “Cory.” Perhaps what I want to say is “Cory/not Cory,” instead of “Cry/don’t Cry.” One could go as far as concluding that I am disappointed at Cory for dueling with death, what I have already mentioned as a do or die play. Is that not a forced and too simple of a conclusion? One could even continue to interpret that the sense of disappointment is directed at myself; that it is “Cory” that is brought in as a mediator between the author’s work and his sense of disappointment in himself. I will stop here and let the task to be continued outside of this art-substrate. In any case the piece has brought to you a do or die instance of its own. We looked through this “hole” together, whether or not it was worth it is left for you to judge. As Cory tried to tell us, “is that not what art is all about?” Is that not the restless duel with art?

Truth belongs to the realm of the signified that reveals itself in the resistances and sometimes in the metonymic structures that reveals the truth and is after the truth. We are used to the real that belongs to the realm of signification. It is through signification that we discover the real. As for our being in the real we experience the truth as it appears. As Lacan says, “truth is always disturbing,” like so I finish the paper on Do or Die.